Menu

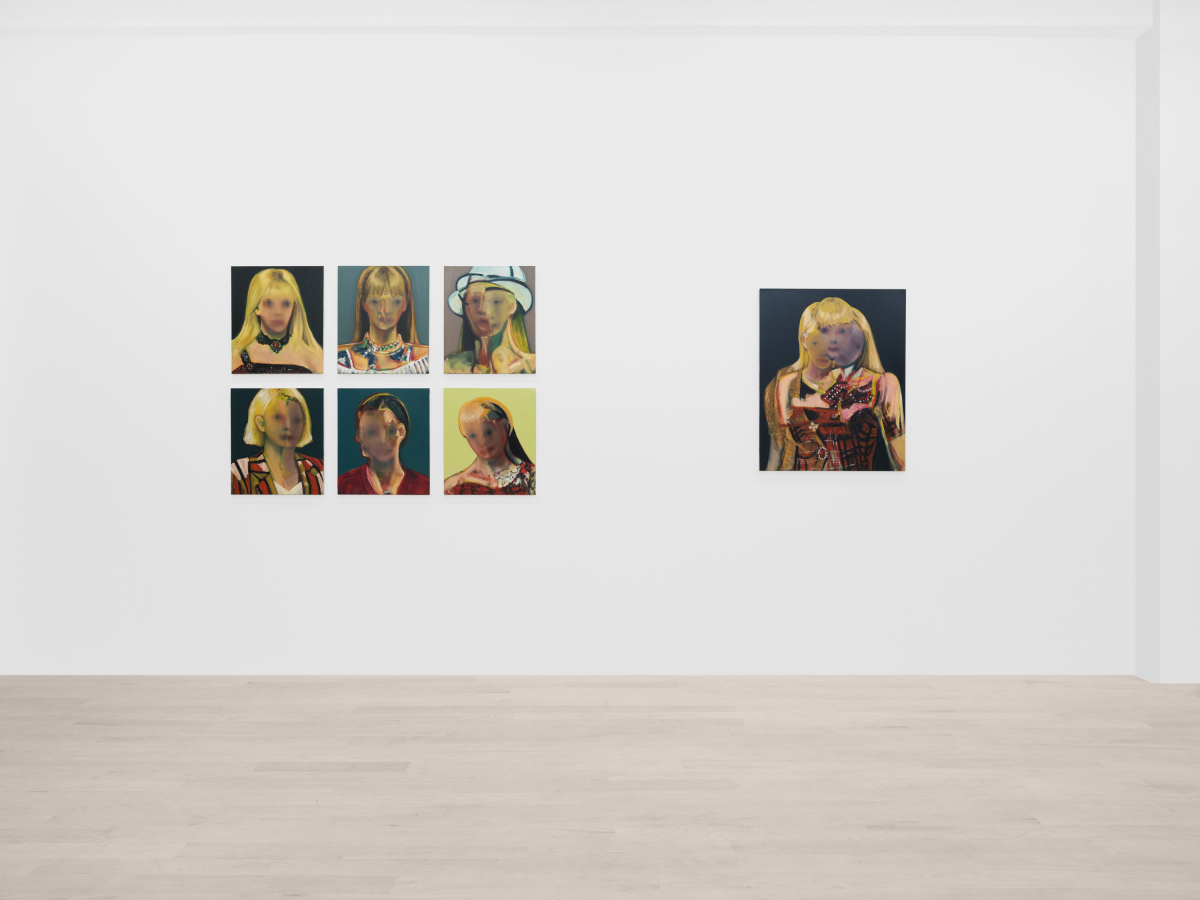

Ghosts in the Garden, Installation View

Management is pleased to present Ghosts in the Garden, Korean painter Jaeheon Lee’s debut exhibition with the gallery. A text by Jungmin Cho accompanies the exhibition.

———

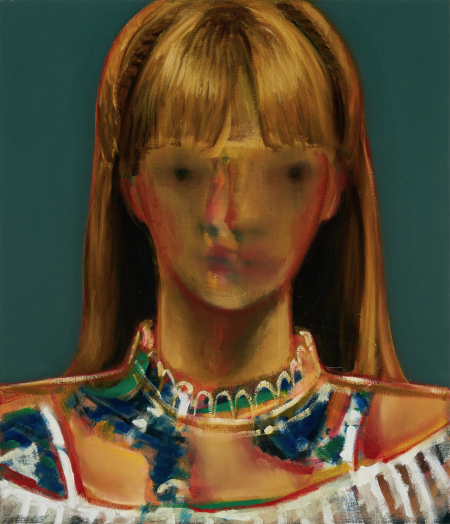

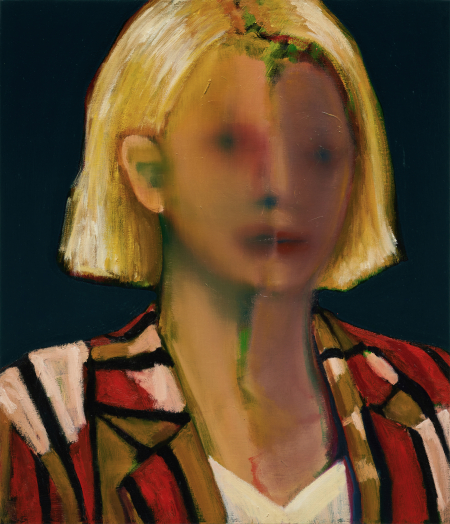

Looking at the paintings of Jaeheon Lee, I always want to follow their gaze, but they slip away from me. They are too still, like fixed dots on the canvas—no more, no less; empty, hollow, blue-green dots. Multiple faces share one body, dressed in the decorative costumes of celebrities in his Idol, Two in One, and Three in One series. In Figure in a Garden, the lush garden of colorful flowers seems to attract so many buzzing bees, almost too loud to listen to. The rough-textured brushstrokes of the background and ornaments are layered upon layers, while the faces seem to exist briefly, then disappear quietly.

The gap created by the contrasting tempo of the background and the figure contains Lee's ongoing contemplation about the disconnection with the past. The type of figurative painting the artist engages in faced a period of marginalization in Korea from the 1960s under the dominance of abstract painting, driven by a desire for modernity and novelty. After Korea's liberation from Japan, the first generation of artists educated in Korea rejected the figurative painting that had been developed under Japanese colonial rule. Instead, they directly embraced contemporary Western art amidst industrialization and modernization, proposing new directions for existing ideologies, art institutions, and artistic styles. Consequently, geometric abstract painting gained attention following its rise internationally, and debates intensified between the old/new generations, academicism/modernism, and figuration/abstraction. In other words, the opposition between figuration and abstraction was embodied in the artistic attitude of the time. Abstraction conveyed the "present and contemporaneity" of Korea in an international language, while figuration expressed Korea's "past and tradition" in its regional language. Although abstract art, through continuous dialogue with the past, came close to the point of convergence with Dansaekhwa, creating a new field for contemporary Korean art, figurative painting has been relatively marginalized, leaving behind faint dialogues within a disconnected timeline.

Lee’s pursuit of figuration has led to the artist’s concern about how he, as someone deeply rooted in Korea, can convey a sense of "Koreanness" through his interpretation of Western visual language. For the artist, this is not about dependence on or nostalgia for the past, but rather a sustained interest and responsibility toward the remnants of art historical rupture to clearly understand the identity of his own practice. With sincere brushstrokes that trace a lineage of traditional Western art history, he seeks to speak to today's Korea. He often draws inspiration from "idols," which he describes as the utmost "Koreanness." Idols, who sing and dance perfectly in glamorous and beautiful outfits, are endlessly consumed and venerated, becoming global icons that undoubtedly represent today’s "K" in Korea. At the same time, implicit sociopolitics hidden within the frame imposed on them under the umbrella of popular culture results in pervasive suffering in our society. Mark Fisher, analyzing today’s pop culture, mentioned in his book on Hauntology that while everyday life has sped up in recent years, culture has slowed down. In the state of continuous connection across time and space facilitated by digital platforms, we repeatedly reproduce and consume culture based on the ghost of the past, becoming increasingly numb to the need for change. In contrast to the accumulating, dazzling superficial background, Lee depicts the inner forms of today’s Korea as rapidly erased, redrawn, consumed, and becoming a void of numbness. Considering how nostalgia-driven pop culture has become a global trend, the void he captures is perhaps not just a story about Korea.

As a result, the void that Lee paints does not remain merely one of nothingness. In his attempt to recover the severed time of figurative painting, and to bridge the gap between tradition and nowness, he deconstructs the historical and psychological void with a deep gaze. This is the portrait of a contemporary painter, as well as of those living in the neoliberal era, who say goodbye to the past, confront their anxieties, and withhold judgment about the future in pursuit of hope. His ongoing act of painting—rooted in reflections on the self, history, and cultural phenomena—is a noble, pilgrimage-like endeavor.

From that moment, a faint stream of cool air begins to seep back into the void. The blurred faces on the canvas start to emerge again. I feel as if I can meet their eyes, piercing through the blue-greenish void.

— Jungmin Cho

Jaeheon Lee (b. 1976 in Ulgin, South Korea) holds an MFA from Seoul National University and is based in Jecheon, South Korea. Solo exhibitions include Ghosts in the Garden at Management, New York; My Ghost at Gallery SP, Seoul; Night Vacuum at Place Mak, Seoul; Abject Beauty at Shin Gallery, New York; Man on the moon at Gallery Chosun, Seoul, and others. Group exhibitions include Time Lapse at PACE, Seoul; The Possible and the Elsewhere at Tang Contemporary Art, Hong Kong; One at a time at WESS, Seoul; Are You Depressed? at Seoul National University Museum of Art; Noon of April at Geomjaejeongseon Art Museum, Seoul; Mindful Mindless at Seoul Olympic Museum of Art; The Secret: Margin of error at Gwangju Museum of Art, the Arko Art Center in Seoul, and the Busan Museum of Art; Ghost House at Jeonbuk Province Art Museum, Jeonju, and others. Lee’s work is in the collections of the Government Art Bank of Korea, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, and the Seoul National University Museum of Art.