Menu

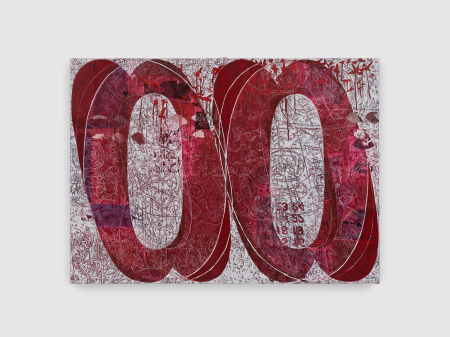

Kate Liebman, Gilgul (The Wheel), Installation View

Management is pleased to present Gilgul (The Wheel), a solo exhibition of new works by New York-based painter Kate Liebman. Her work emerges from a process of meaning-making that weaves together a layered visual tapestry with elements of astronomical charts, Hebraic symbolism, old master paintings of myths, and personal memories. Intelligible despite their complexity, Liebman's paintings are a heuristic bridge between our most confounding mysteries and the defining moments of the human experience. A text by Brooke McGowan accompanies the exhibition.

———

A cacophony of signs haunts the surface.

“It’s instinctual” artist Kate Liebman intones blithely, with a seemingly off handed twirl of her wrist, gesturing towards a tableau in her Brooklyn studio; When it was our generation’s turn to be alive (2025) portrays large, muscular overlapping circling forms, suggestive of at once the plenitude of infinity and the void of zero, against a tangled background of red and burgundy organic forms: a painterly hollow of ghostly tree branches and vines overgrowing the contained field. Immured between layers of white, an image of Bruegel’s masted ship from his masterpiece The Fall of Icarus floats as a memento mori on an ethereal sea, not a bulwark against hubris, but a reminder we will all fall to the earth, unnoticed. On the far left of the canvas, integers, in their rational objectivity, march up the wall like a lie of the mind, pointing towards the ultimate impasse between subjective reality and that which can be weighed, measured, and found wanting. In Zero at the Bone (2025), the numbers repeat, while the round, foregrounded forms of the previous painting give way to delicate red lines, cutting deeper in the flesh of the surface, leaving behind a persistent wound of bright blood-red chroma. The offense, it seems, is so grave as to have violated the substrate itself: barely perceptible beneath the strata of acrylic lies the visceral trace of a wound; the canvas is stitched together by hand. Elsewhere, a cautionary plume of avian forms murmur across the tableau in phase change (2025), met by the whisper of the Hebrew Kaddish, a prayer of mourning: blessed, praised, glorified, exalted, extolled, honored, elevated and lauded be ... Blessed is he. Perhaps, I think to myself, this is also a love letter.

Death, however, is never far off. Indeed, the very title of the exhibition invokes a haunting: Gilgul refers to the mystical Jewish concept of reincarnation, an ancient spectral recycling, subject to a multiplicity of significations. The artist’s use of the Kabbalistic term belies an attraction to its indeterminacy. As the artist states:

‘Wheel’ would be the translation of Gilgul more suggestive of the physical world, ‘cycle’ … more abstract. Perhaps ‘rounds’ would be more sportive and/or more suggestive of medical treatments. This multiplicity is appealing in that it reflects the work both formally (the rounds/cycles/wheels/spinning that make up the compositions) and in process (the iterative approach). Working serially also resonates with this term if you take the concept of reincarnation seriously, because then we are all just iterations of previous and future souls. So then each painting might be thought of as a reiteration of a previous painting, just endlessly shifting from panel to panel.

Composed in the rain shadow of the birth of her two daughters as well as during medical treatments for a loved one, the hauntological works of Gilgul, are undeniably incarnate. These are paintings as flesh, as corpus: bleeding, violated, stitched, marked, reproducing. But these works are also results of an invented, and inventive, process of iteration. After a Lower East Side Printshop residency, Liebman sought to bring the lessons of etching and chinecolle, of putting multiple images on the same plane, back to the studio. The artist first applies to the canvas an assemblage derived from an idiosyncratic library of worked material—the tracing of an MRI of her daughter’s body, a drawing of Grunewald's Isenheim Altarpiece, an image of an airplane, or numbers one through 24 as hours of the day—then washes this with color to create the first archival layer. This prepared ground is subsequently treated with acrylic paint—often white as an undeniable act of erasure. Finally, into that thick, layered body of paint and collage, Liebman carves further signs, like vestiges, wounds, or ghosts. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

Assertive but intimate, hermetic but penetrable, Liebman’s forceful collection of rouge-hued tableaux entices the viewer with a cornucopia of signs whose signification nonetheless withdraws at the very moment of surfacing. The work resists the relentless reduction of the artwork to content, intentional or otherwise. As Susan Sontag states in Against Interpretation, “The overemphasis on the idea of content entails ... the perennial, never consummated project of interpretation.” Such interpretation for Sontag is not only limiting and unitary (looking for only one ‘true’ meaning) but ascetic, overtly rational, or “Even more. It is the revenge of the intellect upon the world. To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world.” This diminishment evolves, for Sontag, from the imagination of a post-mythic consciousness that seeks to strip magic and ritual from art. Thus, while Liebman’s iterative process points towards an indeterminacy which might be understood as traumatic—both personally and existentially—Gilgul, as a body of work and a concept, is recuperative, healing. Through the personal, instinctual, and idiosyncratic, the archeology of Liebman’s oeuvre yearns to excavate the space of the unsayable, to, like the coincidentia oppositorum of zero and infinity, write the sign for the unaccountable—even magical, ritual—without, as Sontag notes, “heroic pretensions or universalist goals.” Or perhaps she is just speaking in tongues.

—Brooke Lynn McGowan